When I wrote that review of Clouds of Witness two and a half years ago I never intended that it would be my last post on the Blue Bore for such a long time. But that is indeed what happened. Now that I look back I’m not exactly sure why. I changed jobs shortly after that post and I suppose that might have had something to do with it. My new (not new anymore) job is much more intense and there’s none of the leisurely lunchtimes dedicated to reading that I used to enjoy before. I kind of love it though, even if it did take away one of the only opportunities I had to settle down with a good book.

I stopped keeping a record of the books that I’ve been reading but I think (based on some very quick notes I’ve just made) I read about 30 books in the interval which is better than I imagined but still not as many as I used to read in one year. There’s no point agonising over it though. It’s been a busy time. Aside from changing jobs, we moved house (twice) and, of course, 2020 happened. I won’t dismiss 2020 as a complete write off because my beautiful, happy baby was born at the start of this epidemic. 2020 has brought lots of reasons to despair but I have something wonderful to be thankful for too.

I’m not sure why I wanted to write this post. I think I just thought I’d like to end things on a slightly tidier note, not with everything hanging in the air post-Wimsey like that. Of course, I don’t know now that I want to end things at all. Maybe I could keep the Blue Bore’s doors open for the occasional update or review, on a purely as-and-when-I can-be-bothered arrangement of course. We shall see what happens.

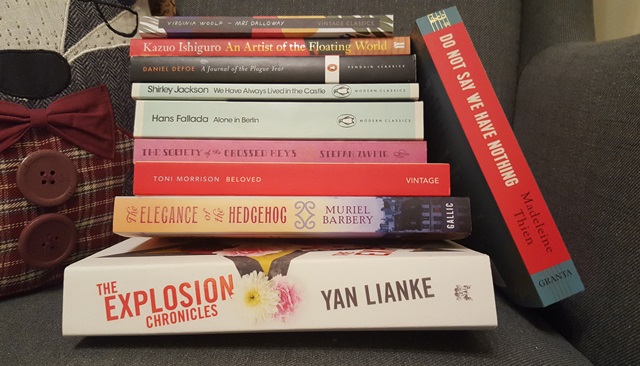

While I mull this over, here are some notable bookish highlights from my time away from the blog. Firstly, the books I remember most fondly are:

Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (2006). Brilliant, brilliant, brilliant. I don’t know what else I can say about it. I have Purple Hibiscus sitting here ready to go but I’m not yet in the headspace for it.

All The Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr (2014). It’s set in St Malo, where I spent many happy summer holidays as a teenager. I love being able to picture where my reads are set, especially one as good as this.

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders (2017). It took me a little while to get my eye in with this one but once everything started falling into place it felt like a very easy but gloriously atmospheric read.

We Have Always Lived In The Castle by Shirley Jackson (1962). Delightfully weird.

In fifth place, I might have In Pursuit of Love by Nancy Mitford or Cranford by Elizabeth Gaskell. I haven’t decided yet. Possibly the latter. I love Miss Matty.

I read five Agatha Christie’s during this time: They Came To Baghdad (silly), Towards Zero (I’ve forgotten it), Murder at the Vicarage (better), And Then There Were None (a new favourite) and Curtain , Poirot’s last case. I knew how that one would end but it was still a bit of a shock. I’m currently reading David Suchet’s book, Poirot & Me, for just a few minutes each night before bed. It’s the only time I get to read at the moment. As a rule I don’t enjoy celebrity autobiographies (or autobiographies at all now that I think about it) but this one has been fine, although I’d have liked more anecdotes about the filming of the TV series than I’m really getting now that I’m further in. I’m a little bit bored of all the non-Poirot related stuff about contracts and theatre performances.

I reread two old favourites. One was When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit, which I remember first getting out of the local library when I was probably about ten or so. My little one is too small to sit still for long enough really but I’ve been reading Mog The Forgetful Cat and The Tiger Who Came To Tea regularly for the past few months in the hope that he will also be a Judith Kerr lover one day. I also reread Jane Eyre, mostly while the baby bump and I were balanced precariously on a lilo in a swimming pool in Cyprus. This was in September last year, but it feels like such a long time ago now.

It occurs to me, after reading through the above, that while I was pregnant I seem to have favoured comfort reads: all five Christies, both of the rereads, Cranford and Good Omens were all read during the long autumn and winter months of my pregnancy. I didn’t realise it at the time but maybe I was just craving cosy reads. Of course, I also read Adam Kaye’s book, This Is Going To Hurt, about a month before I was due to give birth which I realised later was possibly a bad move. I recommend it wholeheartedly, even if that final devastating chapter did put the fear in me for a short time. I’m still favouring the comfort reads at the moment, mainly because I’m perpetually tired but also because the world is just so darn grim at the moment… a happy read every now and again just helps, you know?

Other special mentions go to High Fidelity, Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine and Where do You Go, Bernadette?, all of which I remember enjoying immensely. I also read Daniel Defoe’s 1722 Diary of a Plague Year, although of course I had no idea back then how apt it would prove to be. I should have taken notes.

I think that’s me done, at least for now. I will try to pop back every now and again if I can, although I realise that it’s impossible for me to keep blogging at the same rate I was before. For now, then, goodnight and best wishes to you all. Stay safe.