During the first weeks of the new year I went on a bit of a book buying bender and I’m now feeling quite spent and ashamed of myself. Thankfully the situation is finally under control; I am firmly back on the wagon and have not bought any new books in a month, despite having been sorely tempted on several occasions. Go me.

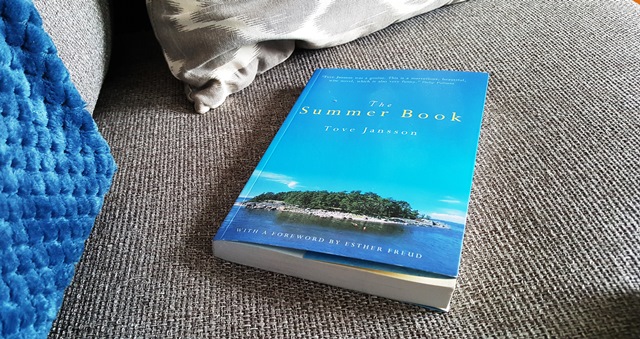

The Summer Book was bought at Waterstones during one of the above sprees. It came down to an agonising toss-up between this and Elizabeth von Armin’s Enchanted April but in the end this was £1 cheaper so… It’s been a welcome addition to my reading year and I kind of love it, which is weird because not a great deal happens at all. This is a semi-fictionalised story set on a tiny island in the Finnish archipelago where Grandmother and six year old Sophia spend their summers. Sophia’s widowed father is also there but he’s almost peripheral; while he works at his desk Sophia and her grandmother potter about the island, exploring, watching the long tailed ducks and quietly enjoying each other’s company.

A write up in The Guardian, written when this book was reissued a few years ago, describes The Summer Book as ‘a butterfly released into a room full of elephants’ and ‘a masterpiece of microcosm, a perfection of the small, quiet read’. I can’t really say it better than that. For me the joy of The Summer Book lies in the simplicity of its central relationship. This gruff old woman, with her aching limbs and her tendency to dwell too much on the past, obviously loves the company of her curious, wilful grandchild, although neither of them would ever admit as much. They’re very similar at heart but Jannson never sentimentalises their relationship, overstates how much they learn from each other or exaggerates Sophia’s childishness. Her humour and lightness of touch are absolutely perfect and make this a really easy, gentle and enjoyable read.

It was quiet again. Sophia stood waiting on the shore where the grass lay stretched on the ground like a light-coloured pelt. And now a new darkness came sweeping over the water – the great storm itself! She ran towards it and was embraced by the wind. She was cold and fiery at the same time and she shouted loudly, “It’s the wind! It’s the wind!” God had sent her a storm of her own.

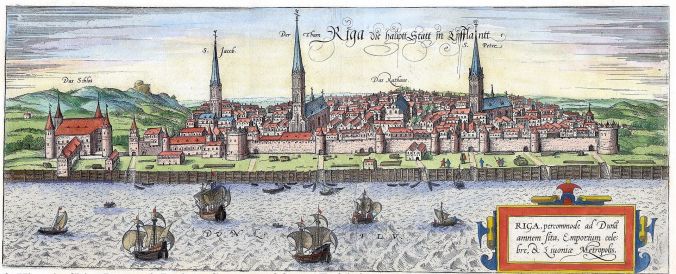

There’s not a thing I can say in criticism of this book which makes this an unusually brief review. Actually that’s not quite true – I can tell you that as a result of this book I ‘wasted’ a good hour on Google images admiring pictures of islands in the Gulf of Finland when I should have been logging onto online banking. The Gulf has now leapfrogged its way up my list of ideal future travel destinations and I am sincerely regretting my lack of funds with which to finance such a visit.